PARSHAT NITZAVIM

November 4, 2021

Making Sense of Mysterious Verses: A Case Study

Daniel Loewenstein

Scholar

The Torah can be hard to relate to at times, for different reasons. Sometimes a law or statement can seem outdated or irrelevant, or even morally confusing. But sometimes the problem is even more basic - we literally just don’t understand what the Torah is saying. The language is cryptic or metaphorical, the word roots are ambiguous, there are twelve missing pronouns - the list goes on. And we throw up our hands and say “This could mean anything!” and then wonder what to do next.

Case Study

Case in point: in this week’s parsha, we’re told that there may be someone whose heart is turned away from God, who tells himself that he can do whatever he wants (i.e. engage in sinful behavior), and he’ll be fine. And the next words are, “למען ספות הרוה את הצמאה,” which means...well, see, that’s the problem.

The best literal translation we can make without making too many assumptions would be something like this:

“So the well watered will sefot [with] the parched.”

And that clearly doesn’t tell us very much. Well watered? Parched? When did we start talking about how hydrated something is? We were talking about sinners thinking they can get away with things.

So...are the “well watered” and “parched” metaphors that have something to do with that? Could be. Let’s assume they are - what do they represent? Not really sure. Okay, maybe the structure of the sentence will give us a clue. What does it say about the well watered and parched? The well watered is going to “sefot” the parched - or, the well watered will get “sefot” just like the parched will. Meaning the relationship is unclear. Well, maybe if we knew what “sefot” meant that would help. It’s not such a common word, though - what does it mean? Good question.

That’s a lot of ambiguity. And there’s actually even more than that. Here’s a (more) complete breakdown of the parts of this verse that are unclear, just in terms of basic meaning:

- What do the well watered and parched represent? It’s safe to assume they represent some sort of metaphor, but we don’t know what it is.

- What does ספות, “sefot,” mean? The root of the verb has a “ס” and a “פ”, but there’s more than one root that uses those letters together.

- How is the word “את” being used here? The word “את” is mostly used as an object marker, but can also sometimes mean “with.”

- What does “so” mean at the beginning of the sentence? The Hebrew word “למען” often indicates a rationale, like the word “so” in the sentence, “He exercised so he’d become healthy.” But it can also indicate an effect, like the word “so” in the sentence, “He exercised, so he became healthy.”

- Who is saying this sentence? Just before this line about the well watered and the parched, we read about the sinner thinking to himself that he could safely do whatever he wanted. So, is our verse a part of that thought? Something the sinner is saying to himself? Or, is it the Torah’s commentary - a statement about the sinner’s thoughts?

Solving the Mystery

With this much uncertainty, it can be very tempting to throw our hands up in desperation. But all is not lost - there’s one valuable, time-honored method for approaching this kind of ambiguity. And it goes like this: you come up with some ideas - a couple of possibilities about what the well watered and parched represent, for example - and then you see how well they fit. Which ones make the verse readable? Which ones fit well in the context? And, for bonus points, which ideas have some outside evidence supporting them - another place in the Torah where “well-watered” means X, or “parched” means Y? And whatever idea fits best - that becomes your working theory. Essentially, it’s a game of trial and error; but it’s the same game physicists play when they develop theories to explain the natural world, or psychologists play when they develop theories about human behavior. It’s all about finding the theory that best explains all the data.

Today, students of the Torah have a great advantage when looking for the best-fitting theory. Because Torah scholars have been generating theories for centuries, and even debating the merits of different theories - and we have access to that. That means we hardly ever have to start from scratch when we encounter an ambiguous verse. It doesn’t necessarily mean we’re limited to considering only the theories that are already on the books - it just means we have a place to start our journey.

So, for example, here’s how some Torah scholars have explained our verse:

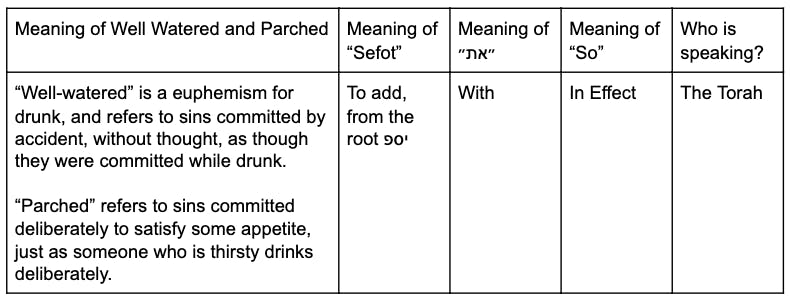

Rashi

Theory: The sinner thinks in his heart that he can do whatever he wants; this will have the effect of God treating any sins committed by accident the same way He treats sins done deliberately (presumably because he would have been happy to do them deliberately).

Answers to the questions:

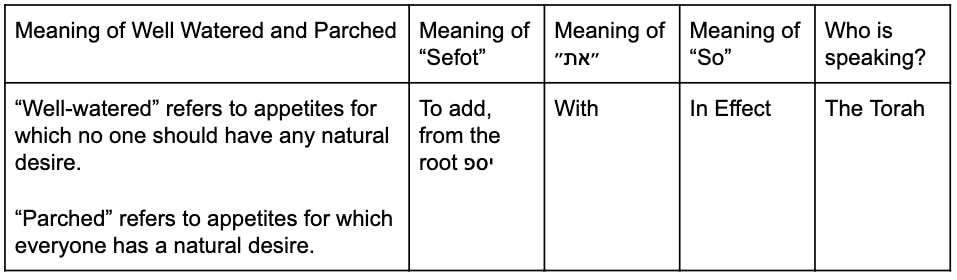

Ramban

Theory: The sinner, by letting his heart’s desires dictate his actions, will indulge so fully (let’s say in food) that he won’t get any satisfaction anymore, and he’ll develop new appetites (let’s say for non-kosher foods) for which he has no inherent natural desires.

Evidence: Other locations in the Bible where “well watered” and “parched” are used to refer to the soul.

Answers to the questions

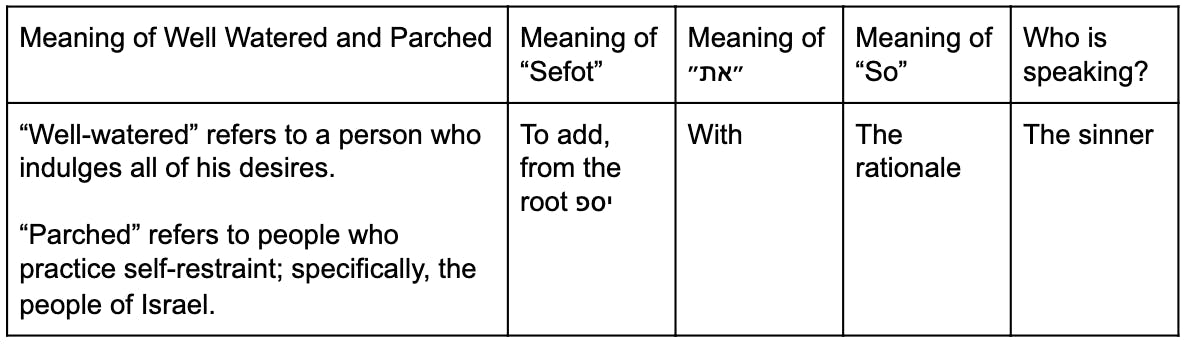

Seforno

Theory: The sinner, by outwardly appearing to be a law-abiding citizen of the Israelite nation, but internally doing whatever he wants, is trying to be fully satisfied but also a part of the nation that practices self-restraint.

Answers to the questions

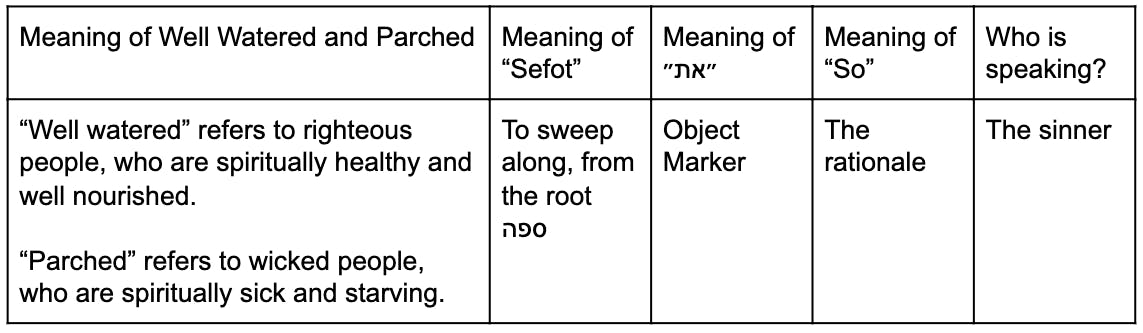

R’ Hirsch

Theory: The sinner thinks that God will not punish him, because he will be swept up with, i.e. will share in, the same general fate of the majority, who are good, law-abiding Israelites.

Answers to the questions

And that’s just four of many theories about the meaning of this mysterious verse.

Drawing Conclusions?

So I mentioned above that when you gather and weigh all your theories, the one that seems to fit best becomes your working theory. But how do you make that call? How do you know what counts as the “best fit”? And who even said you’re supposed to reach a working conclusion? (I know, I know, I did…) Maybe you’re supposed to be happy that you went from having no ideas to several ideas, and leave it at that?

I think that this really has to do with the kind of relationship we’re looking to have with the Torah. And to explain what I mean, let me go back to that useful analogy to theory building in science. When you take an intro course in psychology, you learn about the great debates and issues and the main schools of thought, like the nature-nurture and state-trait questions, or the differences in psychodynamic, social, cognitive and bioecological views of development. You learn about the different kinds of data that each position explains, and how each position makes sense of the data that doesn’t seem to fit. And usually, that’s it. No one is telling you to pick what makes the most sense to you, or even that you can’t believe there’s truth in more than one perspective.

But that changes once you become a researcher or a clinical psychologist. If you’re going to try to build on existing research, to learn new things or to offer people practical help, you really can’t remain agnostic about which perspective is most compelling to you. You have to make a choice. Otherwise, you’ll carry too many possibilities in your head to have any firm sense of whether you’re offering good or bad counsel, or whether your research actually means anything. It’s like trying to get somewhere and constantly changing directions. Now I don’t mean to say that by making a choice, you have to fundamentally discount all other perspectives, that you have to say they’re wrong - it just means that you’ve found what’s most compelling to you. Something you believe enough to build upon.

And I think the same is essentially true in Torah. There’s a way to study Torah that works like a survey course: you learn all the different approaches, maybe even take a stab at adding your own, and leave it at that. In my experience, that’s generally what happens in classes in Orthodox Jewish high schools. And there’s tremendous value in that, in and of itself. But the problem is that if you stay there, there’s a limit to what you can do with Torah in your own life. If you carry all the possibilities of a verse, how do you use that verse to inspire your life? Will you develop practices in line with each of the different possibilities? What if that proves to be impractical, or different reads lead to contradicting conclusions? Or, in a different vein, what if the verse could shed light on another area of Torah - depending on what the verse means? To really delve into something like this, you need to be willing to have enough confidence in an interpretation to follow it through.

And that’s actually what happened as I was developing the ideas in this week’s parsha video. The whole idea in the video is built upon R’ Hirsch’s reading of the verse we’ve been talking about here. And I followed it through, because I had a strong level of confidence in R’ Hirsch’s interpretation. Why? Well, personally, I’m big on grammar, and I know a lot of the classic patterns of verb roots. And - warning, this is about to get a little technical - roots that end in ה tend to look like ספות in the infinitive: בנה ← בנות, קנה ← קנות etc. But roots that start with י tend to look different in the infinitive, with a segol-segol pattern instead of a shva-holam: ילד← לדת, ירד ← רדת. And R’ Hirsch’s explanation was one of the only ones that read ספות as coming from ספה. So that aspect of his interpretation was enough for me to invest in it as my working theory - which led to everything else in the video.

So, next time you come across a mysterious verse, if you feel up to it, try and see which read is most compelling for you - and enjoy the journey it takes you on!